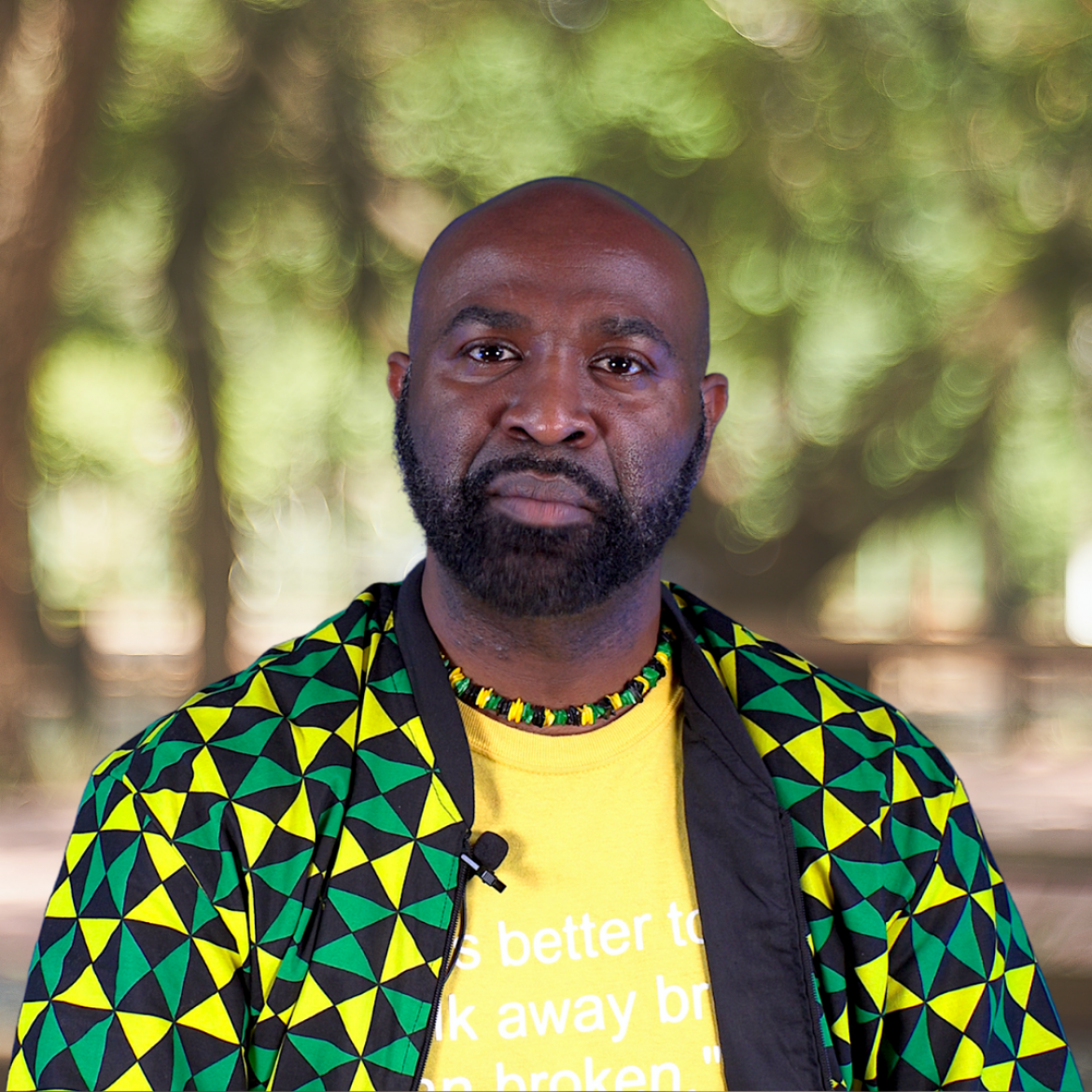

[vc_row css=”.vc_custom_1458549864192{padding-top: 43px !important;padding-left: 10% !important;}”][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”4060″ img_size=”large”][vc_empty_space][vc_column_text]Abidemi Kayode: Teach How To Be A Person[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

“I’m deeply concerned with knowledge. How you acquire knowledge, how you use knowledge, and how you disseminate knowledge.” While it might seem unsurprising that an educator would be interested in all these aspects of knowledge, it is clear that Abidemi Kayode, a school administrator, concern runs much deeper than many in his vocation. Unlike the bulk of them, Abidemi isn’t so much concerned with knowledge learned from books and used to pass tests – dates, equations, etc. – as he is with knowledge about oneself and how to navigate the world one finds oneself in.

This concern springs from Abidemi’s view that “the true definition of education is once you learn what you learn, you’re able to solve your own problems.” Certainly the knowledge of dates, equations, and definitions can help solve problems, but they’re not the panacea that our educational system and society at large seem to treat them as. Giving students, or “scholars” as Abidemi calls them, just this type of knowledge is “like going to Home Depot and grabbing a hammer. But if I don’t know what to do with that hammer, it’s not gonna help me.” If we don’t teach students how to not just research, but research things relevant to the world that they live in, “you’re not truly educating scholars. You’re branding puppets, you’re branding robots, you’re branding workers.”

Currently, Abidemi feels that our educational system really trains people to be subservient individuals, rather than authentic selves. He thinks that this mentality expands beyond schools as well: he himself felt the need to apologize to his son years ago for teaching how to be his son, rather than teaching him how to be a person. Abidemi felt, like many parents do, that they needed to be their child’s first cop and control their actions so that by the time they were old enough to be interacting with real cops they wouldn’t get in trouble. Following that, Abidemi points out “when you send me to school, ok now I’m my teacher’s subordinate. When I go to Sunday school I’m the preacher’s subordinate. When you send me to work, I’ve got a boss there as well. We don’t teach them how to become the people who make a difference in the world.”

—-

Abidemi also notes that our scholastic system, alongside not teaching kids how to use the tools it does offer, provides tools that are very one dimensional. In a counterintuitive way, it tends to give toolboxes to every child that are really best suited for those who need them the least, the ones who are already comfortably living in the world, rather than offering toolboxes for those in deeper need. Similarly, the scholastic systems assumes that all it’s scholars come to school ready to learn. It doesn’t acknowledge that some scholars are hungry all day, or worried about whether or not the electricity will be on when they return home, of almost never see their parent who works two jobs. He sees these economic issues occurring with kids of all races in his schools.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]